In the ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment 2021, the file ‘Impact analysis of the future of home working for cross-border workers after COVID-19’ examined the tax and social security implications of home working by cross-border workers. Hybrid working has the future, so too for the region indicates the SER Opinion ‘Hybrid working’. But home working by cross-border workers can be complex, non-transparent and costly for both employee and employer.

On 15 June 2022, the Next ITEM – Roundtable discussion on Working from home and the issues for frontier workers took place. A closed discussion with employers, MPs, ministries and stakeholders to exchange on the social impact and solution directions. To this end, (large) employers with cross-border workers were invited to reflect on the business and social impact. Some reflections are shared in this contribution.

Working from home is here to stay

On 15 June 2022, the SER presented its advice ‘Hybrid working’ to the Standing Parliamentary Committee on Social Affairs and Employment. The advisory report agrees that working from home is here to stay. Many employees say they want to continue working from home to some extent, and employers are also keen to incorporate it into their business operations. Employers present at the Next ITEM Roundtable also indicated that working from home is here to stay. Reasons for this are that employees are used to it in connection with flexibility and private-work balance, but also from the perspective of reducing commuting (and thus CO2 emissions) and that certain business processes are (by necessity) set up for this purpose. Where working from home was not possible before COVID-19, it is now largely possible within the companies. In a manner of speaking, before COVID-19 for 95% it was not yet possible to work from home, versus after COVID-19 for 95% it is. Where home working is offered, it is eagerly used. COVID-19 has thus left lasting traces in the (new) way of working, which are significantly different from before COVID-19.

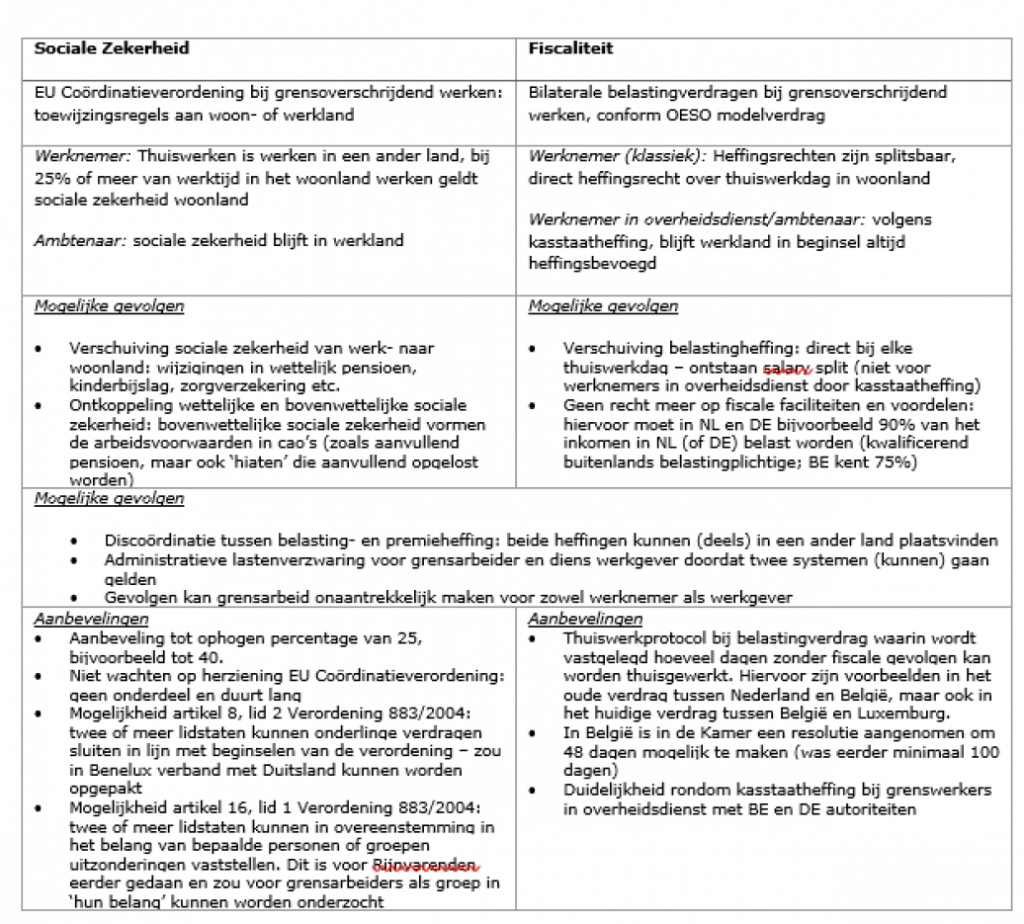

However, cross-border homeworking is not yet a given under the current legislative framework. Indeed, homeworking by cross-border workers is not free of consequences under the normal regulatory framework. The ITEM Cross-Border Impact Assessment elaborates on this. The report shows that the effects are diverse, but in each case the size of the effect varies and whether it is negative or positive (depending on the applicable tax and contribution rate). The table at the bottom of this contribution briefly touches on this point by point. The full study can be found here. See also ITEM puts homework rights cross-border workers on the map and Working from home not obvious for cross-border workers.

Complexity

Regardless of the beneficial or detrimental (net) effects in individual cases, frontier work becomes more complex. Employers also feel responsible for providing the right information, which is impossible due to the many consequences that working from home could have (which cannot be measured merely in net wages) and the required knowledge of administrative requirements and procedures in each Member State. There is little certainty on how to set up homeworking policies for cross-border workers or not so that no unexpected consequences can take place (such as permanent establishment for employer, loss of tax facilities). A key problem

is the availability of full and clear communication on the consequences of working from home and how they can or cannot be avoided, at the tax and social security levels combined.

For multinationals, another element of complexity is what has been communicated at the parent organisation level regarding homeworking. If homeworking is promoted in the organisation at an international level, it creates misunderstanding if it can lead to problems across borders. Employees of a subsidiary derive rights from the communication carried out by the parent organisation. Consequently, many international employees do not understand why working from home would not be possible for them if they live just across the border.

In conclusion, a final element of complexity concerns employers’ duty of care to take good care of the employee through additional conditions in addition to the statutory provisions. The supplementary conditions as laid down in a collective agreement complement the statutory package, including for matters of importance within an organisation. It is considered undesirable if frontier workers would be covered by a different statutory social security, which would lead to uncoordination. It is impossible and undesirable to then impose different additional conditions for frontier workers. Employers want their employees – all of them, frontier worker or not – in one system.

Inequality & Uncertainty

Frontier workers experience uncertainty even while it is still temporarily ineffective (after all, until July 2022, both bilateral tax agreements and unilateral exemption measures to avoid consequences due to COVID-19 apply as farce majeure – for social security, additional exemptions apply from July 2022 to December 2022). The temporariness creates unrest and uncertainty among cross-border workers. This uncertainty is specifically mentioned by cross-border workers in a number of cases as a reason for terminating the employment contract. In general, relatively more employment contract cancellations are observable than, for example, last year (e.g. 20% more cancellations in some cases).

On the other hand, both frontier workers and employers experience a sense of unfairness and inequality. For example, in some organisations, frontier workers are restricted to working from home to, say, 1 day a week or a maximum of 25% once the temporary measures would expire. This is in line with the hard limit in social security under the Coordination Regulation of 25%, see also the table below. In other organisations, no limit or cap has been set, but the limit is effectively/indirectly felt by frontier workers as it would cause a change within taxation and social security. The (mutual) feeling of unequal treatment thus also follows from the current regulatory framework, an external factor outside the employer’s sphere of influence.

Importance of cross-border workers within workforce

For companies on the border in particular, cross-border workers make up a significant proportion of the workforce. The share of cross-border workers varied among the participating companies from 15% to around 40%. The importance of cross-border employment applies to the entire labour market regions on the border. CBS’ Border Data shows that COROP regions on the border in particular have a significant share of cross-border workers. In 2019, many regions had border workers making up at least 1%, with significant outliers in South Limburg (5.5%), Zeeuws-Vlaanderen (4.1%), North Limburg (4.6%), Central Limburg (3.7%) and South-East North Brabant (2.2%).

Therefore, while cross-border employment may seem marginal at the national level, the share is significant at the meso level by region and at the micro level by company.

For certain sectors, the border location has even been the argument for locating in the Dutch border region. For international companies, the international location is desirable to recruit international and/or multilingual staff. On the other hand, the border location makes it possible to recruit the expertise and skills of the workforce across the border. If working from home were no longer possible, it would make it less attractive for companies to establish or stay in the (border) region.

Specifically with regard to the Dutch knowledge economy, it was indicated that about 40% of the employees at Dutch universities are international, many of whom are also cross-border workers. With the European Research Area (ERA), this has always been promoted, with the Netherlands benefiting strongly from incoming international talent, from just across the border or who go to live just across the border.

Concluding: the impact

The Next ITEM Roundtable on Homeworking and Frontier Work brought together employers, stakeholders, experts, ministries and MPs in private and limited setting. The aim was to arrive at an exchange of views and the impact that homeworking by cross-border workers under the current regulatory framework has on the region and employers specifically. After all, as the above points out, cross-border workers working from home have a significant footprint on the regional economy. The entire Dutch labour market is tight, with almost all sectors experiencing staff shortages. CBS recently calculated for the Netherlands that there are 133 vacancies for every 100 unemployed. This also applies to the labour market regions on the national borders. In doing so, border workers are particularly important for these regions to retain and recruit. The cross-border labour force is also an important, if not the most important, pool of labour for many an employer on the Dutch national borders.

However, the very uncertainty and temporary nature of the exceptions has caused cross-border workers to leave organisations and seek employment in their own (home) country. This makes the (border) region less attractive as a business location, which can spiral downwards to the detriment of the regional economy and business activity. Working from home has therefore become an essential prerequisite in the new world of work. The difference from before COVID-19 is significant, both in business processes and mentality. Unhindered facilitation of homeworking by cross-border workers is therefore also desirable not only for the cross-border worker himself, but also for the (knowledge) economy on and across the border as a whole.

On 14 June last, it was announced by Social Affairs and Employment Minister Van Gennip that an agreement was reached at European level by the member states regarding social security. Given the trend that several member states indicated that it would be desirable to better facilitate home working for frontier workers and the observation that it would otherwise become chaotic in several member states, an administrative agreement was reached at EU level (within the Administrative Commission) for the period from July to December 2022. Frontier workers can work from home without consequences, both existing and new frontier workers. The SZW minister’s letter to Eurocommissioner Schmit helped in this regard. The desire from the Netherlands is to use this extra time for a structural arrangement, which is therefore welcome news. It has been indicated from the Ministry of Finance that the temporary tax measures will expire as of July 2022, after which the normal treaty rules will apply again. COVID-19 does not count as a legal basis or farce majeure to deviate from this yet. This position was also communicated in an earlier parliamentary letter. Discussions are taking place with Germany and Belgium to introduce the desirability and possibility of a ‘home working threshold’ in the Tax Treaties, but this still takes time.

While the deal is welcome news for social security, the expiry of the tax derogation agreements as of July has the potential for dis-coordination between taxation and social security, net effects, administrative burden, complexity and loss of tax facilities.[1] While COVID-19 is (currently) no longer a farce majeure to derogate from, critical notes can be raised as to what extent the unprecedented labour market tightness, the socio-economic impact on businesses, border workers and the border region as a whole, and especially the significance with which working and business operations have been changed by COVID-19 cannot be seen as farce majeure in itself. It can also be questioned whether tax fluctuations from exception rules (levy in country of work on home working days; but option), to normal treaty rules (levy in country of residence on home working days), and then in the future to a possible home working threshold (again levy in country of work on home working days; to some extent) should be seen as desirable for both the cross-border worker (changes in tax facilities and net income) and the employer (changes in administrative obligations and burdens).

[1] It should be noted that for civil servants or former civil servants under the Wnra (such as university staff/teachers), a different article of the tax treaty applies and thus, in principle, a cash state levy applies: the country of employment may levy regardless of home working.